Who is Jonathan Meades? He is that man on the telly, who always wears dark suits and talks about stuff you think would be boring but turns out to be really interesting. He performs intellectual acrobatics around a theme and continually re-routes the train-of-thought, sometimes derailing it completely and though you may sometimes feel you are losing track, your train-driver never does. You start out somewhere familiar and soon you have been transported, along with this delightful and well-informed travelling companion, to some surprise destination.

I recall the profound quote from T S Elliot’s The Waste Land, as quoted in the movie The Magus, which was based on the novel by John Fowles and starred Candace Bergan, Anna Karina, Michael Caine and Anthony Quinn:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

This is what Meades facilitates, a meaningfully guided exploration through what might seem mundane towards something that begins to feel magical and when we return to normality, the familiar has become once more fascinating, something much more grotesque and/or beautiful.

Meades is our Media Magus. Indeed he must be working some sort of magic to get his work produced for television. It is difficult to imagine how he might pitch his ideas to producers more usually hungry for increasing viewing figures or sensational tabloid responses… Consider these titles: The Utopian Avoidance of Right Angles, The World of Caravans, The Architecture of Beer, Postwar Churches, The Fens, The Joy of Essex… well, I would want to watch all of those - and the rest of his oeuvre - but I would not have a clue as how to sell these titles to a television producer!

“Well, I have the advantage of having been at it for a long time,” responds Meades with a fatherly tone of encouragement, “I did my first BBC series 25 years ago. I had done a one-off for the BBC before that, and I had done a Channel 4 series before then. So it would not be the same for anyone coming in and trying to do it now – but I still have quite considerable difficulty getting things off the ground. The reviews get better and better and the time I am allotted gets smaller and smaller… but people in television tend not to take any notice of reviews. It’s very, very insular, inward looking, I mean like a verruca – not like a wart, that grows out into something new, more like a verruca that grows inward.”

So, does he suggest that, just perhaps, television companies in general - and the BBC in particular - could be more interested in building internal power structures than in pandering to audiences?

“For example this pathetic nobody called James Harding who had the temerity to criticise Jeremy Paxman - when Paxman said that a lot of the BBC is absolute shite - this little fool rapped his knuckles like some sort of prefect at school… and that is not atypical, it’s pretty much a world that is full of fear and people looking over their shoulders, not wanting to offend. I rather agree with the attitude of Joe Orton and Kingsley Amis that unless you’re offending someone, you’re not doing your job.

“I certainly don’t pander to audiences, I make shows that I want to see, and when I write, I write prose that I would want to read. I mean, you are your own first reader, after all. So I make stuff to please myself, and hope that it will also please a certain audience, and it appears to – I mean, it’s not very large audience…. but that is a self-fulfilling prophecy, when I was on BBC2 I used to get two-and-a-half to three-million viewers, I only get a tenth of that on BBC4, because that is the nature of BBC4. Frankly, I don’t really care – I’m not after viewing figures, I’m after programs and films that please me and please the people I work with.”

Something oft debated, with my students in art history classes, is the question of which is more valid: a piece of work that millions of people think is ‘OK’, or a piece that only a few people respond to, but passionately and on a much deeper level? Generally, to appeal to more people you have to serve a lower common denominator, though true excellence and quality is sometimes, sadly not so often, recognised by the masses.

“My stuff is implicitly critical of television as it is now,” explains Jonathan, “Television used not to be as openly moronic as it has become...

“Obviously, things that appeal to millions of people can be very good, but there is an awful lot of populism which is second-guessing what people are going to like, yet there are lots of unsuccessful light entertainment programs, lots of unsuccessful airport novelists. The thing is that television is so institutionalised that it is very loath to try anything new or to make a program about a subject that has not been covered before. It is very loath to take any risks… and when you think how fantastic it was twenty / twenty-five years ago: we had Denis Potter, Peter Nichols, David Mercer, David Perry, David Rudkin, Tom Stoppard – really good writers writing specially for telly. Whereas now, it has become absolutely formulaic, with very occasional exceptions. I imagine that British television is going to have to react in some way to the success of things like Breaking Bad and The Wire and Lilyhammer and those Scandinavians.”

Yes, those colour-drained crime dramas from the northern lands…

“I don’t think Scandinavian shows are quite what they’re cracked up to be but there is nothing, nothing, made in Britain which is remotely that standard… And television is a great medium. But it has been hijacked by morons.”

|

| RIP - Do you remember Charlie Drake!? |

“There isn’t anything symbolic about it." (Was that a chuckle?) "I want a constant look in those films, and there have been very few when I haven’t worn a dark suit and dark glasses and so on… There is one when I didn’t because someone spilled coffee all over my suit just before I was about to start, so I wore a tweed jacket for that one, which was in Aberdeen… but the suit differentiates me from the few other people who are around and the landscape or streetscape. It turns me into something that may have landed form and alien civilisation. It’s as simple and practical as that.

|

| Jonathan Meades stands out |

“I worked it out. It wasn’t something that I came to by chance, I wanted to do television which was, as much as possible, a kind of one-man-show - performance art as well as being informative, educational, entertaining… and I determined to have that particular look, which I’ve never changed. I hope that it seems like I have come from, elsewhere and I’m very detached from what is around me. Equally, I remember going to see Michel Sardou in concert, a French singer, and he was brilliant on stage. He didn’t do anything, he just stood there absolutely stock still and I found that very impressive.”

Meades manages to be a very detached, yet very human presence throughout his documentaries. In the introduction to the DVD collection he explains how he consciously avoids the TV presenter clichés, always speaking deliberately and eloquently with a very deadpan delivery, so much so that sometimes I get the idea that, just at the point of the edit, he or the cameraman burst out laughing…

“No. Not often, no. The scripts are very written. It is a literary project as well as a visual one. A lot of people who present things on television aren’t writers, they have scripts put together by producers and researchers and so on. What I do is write a very detailed script then give it to the director, who is nearly always Frank Hanley, who is a great friend of mine. Once Frank has got the script I don’t question anything that he does. I do write in a lot of shots and suggestions. But basically after I have written the script, then I am there as actor-performer.”

So the script is of utmost importance here – the words come first. Meades takes great care and puts in the time and effort at the writing stage and thus the rest works out well when interpreted for the screen. So is there a particular approach to writing, a regimen, a Ritual? Or does he just get up, have a coffee and croissant and get on with it.

“I haven’t had a croissant for a long time, very rarely have a croissant… Ritual?” he seems to consider this for a long moment, “No. I just go to work. I get up and I sit down at my computer and start work. I work till lunch time, then do sort of admin things in the afternoon and then, late afternoon, I start writing again. I write very specifically for whatever medium the work I am doing is going to be in. I don’t really believe in synergy between different mediums, I don’t think it works, I think you have to write absolutely specifically. If I am writing for television, it is absolutely specific to television and equally I don’t think my new book or any of my books are particularly adaptable. You could do a version of them but they aren’t written with a view to being re-done.”

So, when he is writing a novel he does not have one eye on the film rights, or TV series?

“Absolutely not, I mean when you take a novel and make a film of it, all you’re left with is the plot, the story and the characters to some extent – you have an element but you don’t have the prose, the nuances of language. I find it rather difficult to understand why there is – always has been – such a reliance on stuff from different media in the cinema. It is a kind of lack of confidence in the power of cinema and similarly in the power of television.

“Y’know this new arts directive announced by the current director general of the BBC is basically TV abasing itself and telling itself that it is not as authentic as theatre or opera or symphonies, and so on – that TV is just a means of transmitting those cultural forms to a bigger audience. That is not right: what TV can do is to create a kind of television that is peculiar to the medium… It is what the writers I mentioned used to do. It is not a poor man’s cinema. It is not radio with pictures. It is something of itself. That is what I, obsessively, try to do… and will sooner or later give up doing because it becomes such a slog!”

So when he does ‘give up’, or if he were to retire – I would very much be interested in the job description used to advertise the vacant position. The most common description of Jonathan Meades seems to be ‘writer and broadcaster’ – I’m not sure it that really covers it.

“I hate the word ‘broadcaster’… I am a… writer and… er… writer. I write books, I write journalism, I write films. I appear in those films but I wouldn’t call myself a ‘broadcaster’ – it’s a deathly sounding word, some terrible fool waving his arms around and speaking a script that’s been written by someone else.

“It’s not my job to classify myself – I do a variety of things. I don’t think about how I should be described. It’s up to other people… I’m not really mad about talking about myself.”

Your new book is all about you…

“It’s not actually, although the title would imply that. It’s much more about my parents and my parents’ generation.”

So An Encyclopaedia of Myself is more of a history book in a way?

“Yeah, it’s a kind of scrutiny of provincial life in the 1950s – it’s very petits pois, very detailed. It is only marginally about me. I’ve only seen the one review so far, in The Sunday Times, which gives the impression that is totally about me – it is not. I am a viewpoint. I am a camera looking at things, I don’t particularly engage…”

Here’s another review from The Guardian…

Perhaps Meades tries not to dwell too much on himself, yet it is his individual take on the subjects he addresses that make him such an asset. He, himself, is the lens that brings many original ideas and fresh views into focus. It has been said that any artist can only ever produce a self-portrait…

“I think that’s true. What Alain Robbe-Grillet said, ‘I have never written about anything except myself.’ People often think there is something distant and objective about his books but there is not and when you realise that, you read them in a different way. It’s more acknowledged in painters than it is in writers, that they have their mark their signatures – you can tell a Cezanne from a Mondrian, I hope. It is evident with painters and I think much less so with writers."

Is there talk of a television series based on An Encyclopaedia of Myself?

"No – it wouldn’t transfer. I mean someone could dramatise it – I could dramatise it, some bits of it – but it is a completely different thing. I have made one or two television films that are autobiographical, one about the places I went to with my father on his rounds selling biscuits in small towns in Hampshire and Dorset and Wiltshire.”

Were those travels with his father responsible for his fascination with how communities were tied together by the way people spoke and the places those people shared familiarity with as a little clan… Within the virtual architecture of video games and our digital viral lives across social media, are we perhaps leaving those little regional differences in the nostalgic past?

“I think that tribalism still exists in Britain. People have regional accents and there are huge regional differences in Britain. Which is something I am so interested in that I wanted to do a series of films about it, but the reaction was, ‘you’re kidding yourself if you think there are these great differences…’ but I think there certainly are. The differences between Newcastle and Plymouth are massive, even down the East Lancs from Liverpool to Manchester – totally different cities.

“Thirty or forty years ago, that tribalism was perhaps disappearing, but it has come back in a very big way. You hear strong regional accents much more than you did for a time and that’s fine. Of course what is not fine about regional accents is the kind of hierarchy that if you have a West Country accent or a Brummie accent you’re not going to get anywhere in life – you have to get rid of it, but that’s not the case with Irish accents or most Welsh accents… Scottish accents or English accents – they’re all OK… but anything with a rural twang, sort of Somerset or Norfolk is deemed unacceptable. There is something very wrong with that – as there is with most hierarchical systems.”

Many people would assume that Meades comes from a privileged upper-class sort of background, but it seems that his childhood at least was quite humble... a working class background?

“Not working class, no, sort of lower middle-class. I mean I would have been entirely state educated if it had not been for my mother having a very rich great uncle. An extraordinary guy. A gay accountant. Basically a gambler who had made a fortune during the depression because he knew how to work stock markets that were constantly falling. So he had made a lot of money and retired at the age of forty with his boyfriend who he called his valet and he used to design outrageous chauffeur uniforms for him. They lived in Dublin, which was apparently a much better place to live if you were gay in those years – there was less persecution of gay people. They used to come to England about once a year in their Rolls Royce and Frank the valet would sit there completely mute, looking like something out of a musical comedy. And he offered to pay the fees for me to go to this really rotten school – really horrible, horrible school – where I felt really out of place because all the other people had fathers who were solicitors, army officers or had their own business. But I am not in the least bit working class, though I did have a West Country accent which I got rid of for those reasons we already discussed. I didn’t sound like Mike Channon – My God Almighty! A huge seagull – just flew towards me. I mean enormous – size of a condor – really big!”

I did not see this bird. Was this one of those hallucinations that he has described in this extract from An Encyclopaedia of Myself, something akin to those flocks of malevolent sheep from the dark side, menacing him along school corridors, or does he have a sea view there?

“From the office I’m in, I am looking out towards a range of hills, and on the other side we look towards the sea.”

This, if you have not already guessed, is a transcription of a transcontinental telephone conversation from the southern coast of France – Marseille(s) where Jonathan Meades for the most part resides – and the heart of Snowdonia where I enjoy an uninterrupted view of the three peaks of the Moelwyns range of mountains… He has mentioned that, as a child, little Jonathan used to think the Devil lived in Blaenau Ffestiniog.

“Yes, when I was a child I thought it was really scary – the slate quarries under a slate coloured sky, y’know, it’s quite something.”

Living and working in a rural area, I have to do quite a bit of driving and I still get a kick out of coming down into the Vale of Ffestiniog, through the Crimea Pass, and when it opens up you can see right down the valley, suddenly it is slate as far as the eye can see… it reminds me of approaching castle Dracula through the Borgo Pass.

“Yes, it is fantastic,” He agrees, “When I took one of my daughters there, she was very… surprised. She hadn’t seen anything like it, and there isn’t much like it.”

Your reasons for moving to France have been explained as ‘gastronomic’…

“No. It was just a whim of wanting to move out of London. There are many parts of Britain which I like very much but are impossible to get in and out of London from. I mean, I love Shropshire, but getting to London from Shropshire takes much longer than getting to London from Marseilles… and flying in is probably cheaper than train tickets from Shropshire too. We looked at places there. I remember looking at a place in Clifton on Teme, which is beautiful, Worcestershire west of the Severn… we were looking at a house there and I asked why ever are you selling it? And they said it just takes too long to get here on the weekend. Britain has really terrible transport infrastructure. It is certainly the worst in Western Europe.”

So how is the ‘Englishman abroad’ thing working out – is there a cultural identity that Meades identifies himself with, or is he becoming a cultural collage?

“I identify myself with my self. I don’t think of myself as English or British or Wiltshire or London, where I lived most of my life… That is something that I am not particularly concerned with.”

Yet the ways that environments affect people, how places and the people who live in them are inextricable linked, is a theme that he has returned to repeatedly.

“Oh, yes. Other people, not me – it’s not something that I really think about. I’m not particularly introspective.”

Talking of environments, does he enjoy living in a building often hailed as one of Le Corbusier’s masterpieces?

“Yes I do.”

Meades manages to be a very detached, yet very human presence throughout his documentaries. In the introduction to the DVD collection he explains how he consciously avoids the TV presenter clichés, always speaking deliberately and eloquently with a very deadpan delivery, so much so that sometimes I get the idea that, just at the point of the edit, he or the cameraman burst out laughing…

|

| Past Presenter... a memento of Meades TV |

|

| A collection of writings including scripts |

“I haven’t had a croissant for a long time, very rarely have a croissant… Ritual?” he seems to consider this for a long moment, “No. I just go to work. I get up and I sit down at my computer and start work. I work till lunch time, then do sort of admin things in the afternoon and then, late afternoon, I start writing again. I write very specifically for whatever medium the work I am doing is going to be in. I don’t really believe in synergy between different mediums, I don’t think it works, I think you have to write absolutely specifically. If I am writing for television, it is absolutely specific to television and equally I don’t think my new book or any of my books are particularly adaptable. You could do a version of them but they aren’t written with a view to being re-done.”

So, when he is writing a novel he does not have one eye on the film rights, or TV series?

“Absolutely not, I mean when you take a novel and make a film of it, all you’re left with is the plot, the story and the characters to some extent – you have an element but you don’t have the prose, the nuances of language. I find it rather difficult to understand why there is – always has been – such a reliance on stuff from different media in the cinema. It is a kind of lack of confidence in the power of cinema and similarly in the power of television.

“Y’know this new arts directive announced by the current director general of the BBC is basically TV abasing itself and telling itself that it is not as authentic as theatre or opera or symphonies, and so on – that TV is just a means of transmitting those cultural forms to a bigger audience. That is not right: what TV can do is to create a kind of television that is peculiar to the medium… It is what the writers I mentioned used to do. It is not a poor man’s cinema. It is not radio with pictures. It is something of itself. That is what I, obsessively, try to do… and will sooner or later give up doing because it becomes such a slog!”

So when he does ‘give up’, or if he were to retire – I would very much be interested in the job description used to advertise the vacant position. The most common description of Jonathan Meades seems to be ‘writer and broadcaster’ – I’m not sure it that really covers it.

“I hate the word ‘broadcaster’… I am a… writer and… er… writer. I write books, I write journalism, I write films. I appear in those films but I wouldn’t call myself a ‘broadcaster’ – it’s a deathly sounding word, some terrible fool waving his arms around and speaking a script that’s been written by someone else.

“It’s not my job to classify myself – I do a variety of things. I don’t think about how I should be described. It’s up to other people… I’m not really mad about talking about myself.”

Your new book is all about you…

“It’s not actually, although the title would imply that. It’s much more about my parents and my parents’ generation.”

|

| What's it about, Jonathan? |

“Yeah, it’s a kind of scrutiny of provincial life in the 1950s – it’s very petits pois, very detailed. It is only marginally about me. I’ve only seen the one review so far, in The Sunday Times, which gives the impression that is totally about me – it is not. I am a viewpoint. I am a camera looking at things, I don’t particularly engage…”

Here’s another review from The Guardian…

Perhaps Meades tries not to dwell too much on himself, yet it is his individual take on the subjects he addresses that make him such an asset. He, himself, is the lens that brings many original ideas and fresh views into focus. It has been said that any artist can only ever produce a self-portrait…

“I think that’s true. What Alain Robbe-Grillet said, ‘I have never written about anything except myself.’ People often think there is something distant and objective about his books but there is not and when you realise that, you read them in a different way. It’s more acknowledged in painters than it is in writers, that they have their mark their signatures – you can tell a Cezanne from a Mondrian, I hope. It is evident with painters and I think much less so with writers."

Is there talk of a television series based on An Encyclopaedia of Myself?

"No – it wouldn’t transfer. I mean someone could dramatise it – I could dramatise it, some bits of it – but it is a completely different thing. I have made one or two television films that are autobiographical, one about the places I went to with my father on his rounds selling biscuits in small towns in Hampshire and Dorset and Wiltshire.”

Were those travels with his father responsible for his fascination with how communities were tied together by the way people spoke and the places those people shared familiarity with as a little clan… Within the virtual architecture of video games and our digital viral lives across social media, are we perhaps leaving those little regional differences in the nostalgic past?

“I think that tribalism still exists in Britain. People have regional accents and there are huge regional differences in Britain. Which is something I am so interested in that I wanted to do a series of films about it, but the reaction was, ‘you’re kidding yourself if you think there are these great differences…’ but I think there certainly are. The differences between Newcastle and Plymouth are massive, even down the East Lancs from Liverpool to Manchester – totally different cities.

“Thirty or forty years ago, that tribalism was perhaps disappearing, but it has come back in a very big way. You hear strong regional accents much more than you did for a time and that’s fine. Of course what is not fine about regional accents is the kind of hierarchy that if you have a West Country accent or a Brummie accent you’re not going to get anywhere in life – you have to get rid of it, but that’s not the case with Irish accents or most Welsh accents… Scottish accents or English accents – they’re all OK… but anything with a rural twang, sort of Somerset or Norfolk is deemed unacceptable. There is something very wrong with that – as there is with most hierarchical systems.”

Many people would assume that Meades comes from a privileged upper-class sort of background, but it seems that his childhood at least was quite humble... a working class background?

“Not working class, no, sort of lower middle-class. I mean I would have been entirely state educated if it had not been for my mother having a very rich great uncle. An extraordinary guy. A gay accountant. Basically a gambler who had made a fortune during the depression because he knew how to work stock markets that were constantly falling. So he had made a lot of money and retired at the age of forty with his boyfriend who he called his valet and he used to design outrageous chauffeur uniforms for him. They lived in Dublin, which was apparently a much better place to live if you were gay in those years – there was less persecution of gay people. They used to come to England about once a year in their Rolls Royce and Frank the valet would sit there completely mute, looking like something out of a musical comedy. And he offered to pay the fees for me to go to this really rotten school – really horrible, horrible school – where I felt really out of place because all the other people had fathers who were solicitors, army officers or had their own business. But I am not in the least bit working class, though I did have a West Country accent which I got rid of for those reasons we already discussed. I didn’t sound like Mike Channon – My God Almighty! A huge seagull – just flew towards me. I mean enormous – size of a condor – really big!”

I did not see this bird. Was this one of those hallucinations that he has described in this extract from An Encyclopaedia of Myself, something akin to those flocks of malevolent sheep from the dark side, menacing him along school corridors, or does he have a sea view there?

“From the office I’m in, I am looking out towards a range of hills, and on the other side we look towards the sea.”

This, if you have not already guessed, is a transcription of a transcontinental telephone conversation from the southern coast of France – Marseille(s) where Jonathan Meades for the most part resides – and the heart of Snowdonia where I enjoy an uninterrupted view of the three peaks of the Moelwyns range of mountains… He has mentioned that, as a child, little Jonathan used to think the Devil lived in Blaenau Ffestiniog.

“Yes, when I was a child I thought it was really scary – the slate quarries under a slate coloured sky, y’know, it’s quite something.”

Living and working in a rural area, I have to do quite a bit of driving and I still get a kick out of coming down into the Vale of Ffestiniog, through the Crimea Pass, and when it opens up you can see right down the valley, suddenly it is slate as far as the eye can see… it reminds me of approaching castle Dracula through the Borgo Pass.

“Yes, it is fantastic,” He agrees, “When I took one of my daughters there, she was very… surprised. She hadn’t seen anything like it, and there isn’t much like it.”

Your reasons for moving to France have been explained as ‘gastronomic’…

“No. It was just a whim of wanting to move out of London. There are many parts of Britain which I like very much but are impossible to get in and out of London from. I mean, I love Shropshire, but getting to London from Shropshire takes much longer than getting to London from Marseilles… and flying in is probably cheaper than train tickets from Shropshire too. We looked at places there. I remember looking at a place in Clifton on Teme, which is beautiful, Worcestershire west of the Severn… we were looking at a house there and I asked why ever are you selling it? And they said it just takes too long to get here on the weekend. Britain has really terrible transport infrastructure. It is certainly the worst in Western Europe.”

So how is the ‘Englishman abroad’ thing working out – is there a cultural identity that Meades identifies himself with, or is he becoming a cultural collage?

“I identify myself with my self. I don’t think of myself as English or British or Wiltshire or London, where I lived most of my life… That is something that I am not particularly concerned with.”

Yet the ways that environments affect people, how places and the people who live in them are inextricable linked, is a theme that he has returned to repeatedly.

“Oh, yes. Other people, not me – it’s not something that I really think about. I’m not particularly introspective.”

Talking of environments, does he enjoy living in a building often hailed as one of Le Corbusier’s masterpieces?

“Yes I do.”

Was living in La Cité Radieuse, apparently referred to by some locals as ‘The Crackpot’s House’, justified as research for Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry – his most recent two-part television exploration?

“Oh, no, much longer ago than that. But the Brutalism programme was something I had been thinking of for a long time – in 1994, I did a film called Jerry Building about Hitler’s architecture, and that alludes to the fact that the bunkers and defensive structures of that regime were the precursors of the Brutalism of the 1960s and 70s and there was a fairly considerable interest taken in them. People rather ignored all of those structures for a long time and then the French writer and theorist Paul Virilio wrote a book called Bunkerology and that was the culmination of his research into bunkers. What he did was start to take photographs of them and publish them in architectural magazines and it awakened quite a considerable interest and so there is that route into Brutalism from the bunkers. His earliest photographs of bunkers were in the early 1960s and his book didn’t come out until the early 1970s. Not a very good photographer it has to be said, but that isn’t particularly pertinent. He designed, with Claude Parent a very bunker-like church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay in Nevers, Northern Burgundy.”

Having looked at Bauhaus and Modern architecture over the years, teaching and giving talks about them, I have grown to appreciate Corbusier-style buildings - in the right place. I particularly admire some of the ideas in his Sainte-Marie de la Tourette for example. Concrete Brutalism seems to work well against a rural setting, when counterpointed by rolling hills, or trees and natural dry-stone walling, something to balance the expanses of grey and flat slabs, but too much together in a city centre gets rather drab, oppressive and overwhelming…

“Oh, no, much longer ago than that. But the Brutalism programme was something I had been thinking of for a long time – in 1994, I did a film called Jerry Building about Hitler’s architecture, and that alludes to the fact that the bunkers and defensive structures of that regime were the precursors of the Brutalism of the 1960s and 70s and there was a fairly considerable interest taken in them. People rather ignored all of those structures for a long time and then the French writer and theorist Paul Virilio wrote a book called Bunkerology and that was the culmination of his research into bunkers. What he did was start to take photographs of them and publish them in architectural magazines and it awakened quite a considerable interest and so there is that route into Brutalism from the bunkers. His earliest photographs of bunkers were in the early 1960s and his book didn’t come out until the early 1970s. Not a very good photographer it has to be said, but that isn’t particularly pertinent. He designed, with Claude Parent a very bunker-like church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay in Nevers, Northern Burgundy.”

Having looked at Bauhaus and Modern architecture over the years, teaching and giving talks about them, I have grown to appreciate Corbusier-style buildings - in the right place. I particularly admire some of the ideas in his Sainte-Marie de la Tourette for example. Concrete Brutalism seems to work well against a rural setting, when counterpointed by rolling hills, or trees and natural dry-stone walling, something to balance the expanses of grey and flat slabs, but too much together in a city centre gets rather drab, oppressive and overwhelming…

“Yes, but he can’t be blamed for what his imitators did. He had thousands of imitators and about five percent of them were good, the rest were rather mediocre. There’s a lot of very bad sub-Corbusien building in virtually every country in the world.”

For a fairly brief part of my childhood I lived in ‘Skem’ (Skelmersdale) one of the 1970s concrete and pebble-dash New Towns, hailed as ‘the future’, the way we would all be living… but did not really catch on, did it?

“Well, some of them did and some of them didn’t. With most of these social housing projects of the fifties, sixties and seventies, you had architects who were extremely well intentioned being undercut all the time by politicians wanting to get things done cheaper. Local councils who were charged with maintaining these places didn’t do so. If you buy a car, you then get it regularly serviced, but these places were not serviced. They were also completely undefended, anyone could walk in and have a piss in the lift, and they did. But it needn’t have been like that. High-rise works very well for the rich – you only have to look at London or New York nearly any big city except Paris - which doesn’t really have a lot of high-rise in the centre and has a different demographic pattern. But rich people always get on very well in social housing because their places are looked after by concierges and janitors and so on and not anyone can just walk in – it’s not a free space, it is a gated community avant la lettre… and those new towns would have worked just as well if that had been noted.”

Architecture is an interest I share with Meades, but I remember this interview is for Scrawl, so I attempt to steer it back to his word-wielding and creative writing. Filthy English is one of my favourite anthologies of short fiction and is a potent and very dark portrait of ‘Englishness’, both the language and the (sub)culture. The stories are sparked by etymological meanings, this in itself is an intriguingly Post-Modern method of approaching literature…

“The title story is,” Meades agrees to some extent, “I don’t think the other stories in the collection are really… the story set in the New Forest - that is based on stuff I gleaned from my mother who taught in the New Forest early in the Second World War.”

He is talking about The Sylvan Life, the second story from the Filthy English collection, in which some of the children wear itchy, untreated wild animal furs as underwear (which is the least of their problems)… Just one example, and not the strongest by far, of disturbing elements in a lot of his fiction… It always has plenty of humour, but a lot of darkness that I think qualifies Meades as a horror writer…

“That’s certainly true, but a lot of it is fact or has been recounted to me. The thing about the children coming to school sewn into furs, that’s something my mother told me, it came with my mother’s milk, so to speak. Quite a lot of the stuff in that book, and in Pompey and Fowler Family Business, comes from stuff that people have told me – I’m quite a sponge – I remember what people tell me.

“For instance the most singularly horrific thing in Pompey is the guy who chokes to death on his own shit. Well, that actually happened… I was talking to a writer friend of mine and he said, ‘A most extraordinary thing has happened – this was in Herefordshire, the Welsh Marches – a guy, who was a local bastion at the chamber of commerce and a magistrate, had this particular predilection for shoving a pipe up his arse and then sucking on it, a kind of self-enema, and he choked to death on it.’ I said to my friend, ‘God, what a gift that is!’ He asked, ‘What do you mean?’ I was talking from the point of view of a writer and I said, ‘Well aren’t you going to use it?’ and he said, ‘Oh no, you have it!’ So I did.

“There is a great deal of stuff that comes, not from my life, but anecdotally received incidents from the lives of others. A lot of the stuff in those stories is invented, the places almost certainly aren’t. Even when I’m writing about the Congo, somewhere I’ve never been, or Agadir – I’ll have done quite a lot of reading round a subject to try to get it right. Every book swallows hundreds of other books so… if I was writing a book about someone who steals eggs, I wouldn’t read another book about an egg-stealer, but I would read about chicken runs or how to construct them… how you could get grants to build chicken runs after the first world war, and things like that. That’s what I do with my films as well, taking an oblique view, not going directly into the subject but looking at things that are tangential to the subject.”

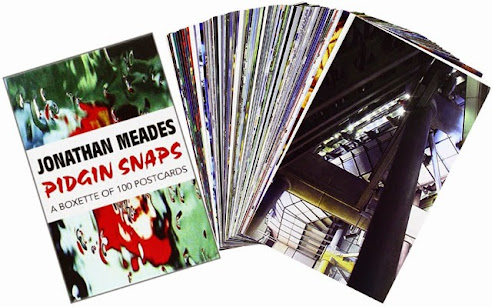

Speaking of tangents, Meades also enjoys working in varied creative formats – I recently enjoyed Pidgin Snaps: A Boxette, his collection of photography presented as 100 postcards (you can read my review here), I know he also dabbles with drawing and painting…

For a fairly brief part of my childhood I lived in ‘Skem’ (Skelmersdale) one of the 1970s concrete and pebble-dash New Towns, hailed as ‘the future’, the way we would all be living… but did not really catch on, did it?

“Well, some of them did and some of them didn’t. With most of these social housing projects of the fifties, sixties and seventies, you had architects who were extremely well intentioned being undercut all the time by politicians wanting to get things done cheaper. Local councils who were charged with maintaining these places didn’t do so. If you buy a car, you then get it regularly serviced, but these places were not serviced. They were also completely undefended, anyone could walk in and have a piss in the lift, and they did. But it needn’t have been like that. High-rise works very well for the rich – you only have to look at London or New York nearly any big city except Paris - which doesn’t really have a lot of high-rise in the centre and has a different demographic pattern. But rich people always get on very well in social housing because their places are looked after by concierges and janitors and so on and not anyone can just walk in – it’s not a free space, it is a gated community avant la lettre… and those new towns would have worked just as well if that had been noted.”

Architecture is an interest I share with Meades, but I remember this interview is for Scrawl, so I attempt to steer it back to his word-wielding and creative writing. Filthy English is one of my favourite anthologies of short fiction and is a potent and very dark portrait of ‘Englishness’, both the language and the (sub)culture. The stories are sparked by etymological meanings, this in itself is an intriguingly Post-Modern method of approaching literature…

“The title story is,” Meades agrees to some extent, “I don’t think the other stories in the collection are really… the story set in the New Forest - that is based on stuff I gleaned from my mother who taught in the New Forest early in the Second World War.”

He is talking about The Sylvan Life, the second story from the Filthy English collection, in which some of the children wear itchy, untreated wild animal furs as underwear (which is the least of their problems)… Just one example, and not the strongest by far, of disturbing elements in a lot of his fiction… It always has plenty of humour, but a lot of darkness that I think qualifies Meades as a horror writer…

|

| The Horror... The Humour... |

“For instance the most singularly horrific thing in Pompey is the guy who chokes to death on his own shit. Well, that actually happened… I was talking to a writer friend of mine and he said, ‘A most extraordinary thing has happened – this was in Herefordshire, the Welsh Marches – a guy, who was a local bastion at the chamber of commerce and a magistrate, had this particular predilection for shoving a pipe up his arse and then sucking on it, a kind of self-enema, and he choked to death on it.’ I said to my friend, ‘God, what a gift that is!’ He asked, ‘What do you mean?’ I was talking from the point of view of a writer and I said, ‘Well aren’t you going to use it?’ and he said, ‘Oh no, you have it!’ So I did.

|

| Some good shit... |

Speaking of tangents, Meades also enjoys working in varied creative formats – I recently enjoyed Pidgin Snaps: A Boxette, his collection of photography presented as 100 postcards (you can read my review here), I know he also dabbles with drawing and painting…

“What the French would call en catimini, which is to say on the sly, with no pretensions. I take photographs fairly obsessively and I do paint a bit. I started taking photographs in car washes, as one does, you get extraordinary effects. Then I started putting liquids of different colours and viscosity into plastic bags and taking photographs of that. Looking at surfaces and making things… so it is all representational but looks like instant abstract expressionism in some cases.

“It amuses me but - I am very perfectionist and detailed as a writer and I will spend hours on a sentence or paragraph getting it right. But with this stuff I do it sort of left-handed and don’t really care what the result is, but in my writing and in my television there is no room for spontaneity, everything is worked out in advance. With this there is a kind of spontaneity that is quite liberating in a way – just messing around."

Some teachers of creative writing do recommend painting and drawing - working with your hands and eyes can bring in fresh creative faculties and get different parts of the brain going…

“Absolutely true it does – what I’ve got left that isn’t atrophied yet – it helps find bits that are actually quite useful which I might not have previously explored.”

Are there any favourite visual artists or ones that Meades finds particularly inspiring?

“They do inspire me, yes, but not to emulate them, but they inspire me, full stop. I find them uplifting: Otto Dix, Christian Schad, Rogier van der Weyden, people who work in extreme detail – though Bacon I find splendid, perhaps the greatest artist of the twentieth century."

You see, I would have thought more Modernist, with his preferences in architecture… Minimalists, Malevich, and Mondrian...

“I’m not very interested in that – I like representational painting really. Pollock and DeKooning leave me cold. I like painters like Edward Burra, one of those eccentric odd-ball English people – not really part of the great canon. I hate this idea of minor painters, or minor poets, I think Burra was terrific. Carel Willink, Dick Ket, and the so called Magical Realists in Holland in the 1930s and 1940s, very interesting – they are rather like the German Neue Sachlichkeit but without the same bitterness.

“I have thousands of postcards, many of them from art galleries and have these weird plastic folders suspended from the ceiling which just show cards on both sides – the one closest to me at the moment has got a portrait of Martin Luther, a painting by Christian Schad, a painting by some Victorian whose name I don’t know, something by one of the Birmingham School who are kind of slightly like Beardsley without the pornographic element, something by a woodcut artist whose work I found in Lubeck, something by Nevinson, another one by Nevinson, a Victorian narrative painting of the Princes in the Tower, something by Patrick Caulfield – very eclectic, I mean I don’t really believe in ‘schools’ I believe in talents. Schools and -isms are quite interesting in a way, but it is just a form of taxonomy which is like when you asked to describe myself – well I don’t.

“It’s like the Nouveau Roman, Alan Robbe-Grillet was fantastic, a great, great artist and writer, but the rest of those people – Jesus, they were so boring, plodding, nothing to say, whereas he was a wonderful kind of poet. I do find it very weird that many architects will say, ‘Oh, I’m a Corbusian’, or ‘I’m a Miesian’, or ‘I follow Lloyd Wright’, for example.

“I find that very strange – because writers don’t think in that way and painters don’t think in that way. They don’t say, ‘Oh, I want to paint like… Constable,’ or, ‘I want to paint like Motherwell,’ – they just want to paint. And for the most part, I don’t think writers sit down and think, ‘I want to be like Stevenson.’ Perhaps when you’re starting off you might – it was Stevenson who said, ‘You teach yourself by being the sedulous ape, you can’t help mimic people until you find your own voice,’ and I think there is truth in that, but afterwards you wouldn’t dream of sitting down and thinking, ‘I’m going to write this paragraph like Fitzgerald’…

“Most creatives are obsessed with trying to be true to themselves, and one way of being like yourself is like what Picasso said, ‘copy anyone, but never copy yourself.’ Picasso copied Velázquez - coming out as Picasso of course, but that can be a route into finding a different part of yourself.”

After a writing career spanning three-and-a-half decades, does Jonathan have any advice for aspiring writers?

“Get a job in the city. I think things are worse for writers than they have been for a long time because of things like blogging – which is a form of self-publishing – people are not able to make any kind of living from writing, which can be arduous and takes a long time – perhaps it doesn’t take bloggers a long time and there are different types of blogger, so I don’t know – The old phrase was, ‘Write for pleasure, publish for profit,’ – now its write for pleasure and publish for pleasure."

The ease of publishing nowadays is good in many respects. Power has been returned to the writer and things with limited minority appeal can now be put out cost-effectively, but it also means that we are swamped by masses of unmediated stuff that readers have to navigate for themselves, without the filters of publishing houses…

“Yes, but the publishing houses have always been very fallible – they have no idea. If they get a best seller, they just try to repeat the formula. That’s no different from TV.”

Different is something that Jonathan Meades is. His fiction is certainly not formulaic. His television is far from being run-of-the-mill. His mind has the elements of wonder and curiosity of a young child, and the cutting intellect of a polymath with wide-ranging experiences. He uses words well, though it is hard to sum him up with them…

‘Etymological’ is an interesting word, sounds so much like ‘entomology’ that some people mite (sic) get confused, it’s the word for the study of words, how post-modern and self-referential is that? Of course, Meades would never get confused by this sort of thing, being an expert etymological archaeologist and Media Magus… I wonder does he have a favourite word?

“No.”

No? ‘No’ – that’s his favourite word? (Titles spring to mind for this interview feature: Jonathan Meades – the man who likes to say NO… Doctor NO… Mr NO it all… NO Meades NO… Or did he actually say, ‘Know’? Now, that’s more like it…)

“No, it’s not. I really don’t have a favourite word!”

“It amuses me but - I am very perfectionist and detailed as a writer and I will spend hours on a sentence or paragraph getting it right. But with this stuff I do it sort of left-handed and don’t really care what the result is, but in my writing and in my television there is no room for spontaneity, everything is worked out in advance. With this there is a kind of spontaneity that is quite liberating in a way – just messing around."

Some teachers of creative writing do recommend painting and drawing - working with your hands and eyes can bring in fresh creative faculties and get different parts of the brain going…

“Absolutely true it does – what I’ve got left that isn’t atrophied yet – it helps find bits that are actually quite useful which I might not have previously explored.”

Are there any favourite visual artists or ones that Meades finds particularly inspiring?

“They do inspire me, yes, but not to emulate them, but they inspire me, full stop. I find them uplifting: Otto Dix, Christian Schad, Rogier van der Weyden, people who work in extreme detail – though Bacon I find splendid, perhaps the greatest artist of the twentieth century."

You see, I would have thought more Modernist, with his preferences in architecture… Minimalists, Malevich, and Mondrian...

“I’m not very interested in that – I like representational painting really. Pollock and DeKooning leave me cold. I like painters like Edward Burra, one of those eccentric odd-ball English people – not really part of the great canon. I hate this idea of minor painters, or minor poets, I think Burra was terrific. Carel Willink, Dick Ket, and the so called Magical Realists in Holland in the 1930s and 1940s, very interesting – they are rather like the German Neue Sachlichkeit but without the same bitterness.

“I have thousands of postcards, many of them from art galleries and have these weird plastic folders suspended from the ceiling which just show cards on both sides – the one closest to me at the moment has got a portrait of Martin Luther, a painting by Christian Schad, a painting by some Victorian whose name I don’t know, something by one of the Birmingham School who are kind of slightly like Beardsley without the pornographic element, something by a woodcut artist whose work I found in Lubeck, something by Nevinson, another one by Nevinson, a Victorian narrative painting of the Princes in the Tower, something by Patrick Caulfield – very eclectic, I mean I don’t really believe in ‘schools’ I believe in talents. Schools and -isms are quite interesting in a way, but it is just a form of taxonomy which is like when you asked to describe myself – well I don’t.

“It’s like the Nouveau Roman, Alan Robbe-Grillet was fantastic, a great, great artist and writer, but the rest of those people – Jesus, they were so boring, plodding, nothing to say, whereas he was a wonderful kind of poet. I do find it very weird that many architects will say, ‘Oh, I’m a Corbusian’, or ‘I’m a Miesian’, or ‘I follow Lloyd Wright’, for example.

“I find that very strange – because writers don’t think in that way and painters don’t think in that way. They don’t say, ‘Oh, I want to paint like… Constable,’ or, ‘I want to paint like Motherwell,’ – they just want to paint. And for the most part, I don’t think writers sit down and think, ‘I want to be like Stevenson.’ Perhaps when you’re starting off you might – it was Stevenson who said, ‘You teach yourself by being the sedulous ape, you can’t help mimic people until you find your own voice,’ and I think there is truth in that, but afterwards you wouldn’t dream of sitting down and thinking, ‘I’m going to write this paragraph like Fitzgerald’…

“Most creatives are obsessed with trying to be true to themselves, and one way of being like yourself is like what Picasso said, ‘copy anyone, but never copy yourself.’ Picasso copied Velázquez - coming out as Picasso of course, but that can be a route into finding a different part of yourself.”

After a writing career spanning three-and-a-half decades, does Jonathan have any advice for aspiring writers?

“Get a job in the city. I think things are worse for writers than they have been for a long time because of things like blogging – which is a form of self-publishing – people are not able to make any kind of living from writing, which can be arduous and takes a long time – perhaps it doesn’t take bloggers a long time and there are different types of blogger, so I don’t know – The old phrase was, ‘Write for pleasure, publish for profit,’ – now its write for pleasure and publish for pleasure."

The ease of publishing nowadays is good in many respects. Power has been returned to the writer and things with limited minority appeal can now be put out cost-effectively, but it also means that we are swamped by masses of unmediated stuff that readers have to navigate for themselves, without the filters of publishing houses…

“Yes, but the publishing houses have always been very fallible – they have no idea. If they get a best seller, they just try to repeat the formula. That’s no different from TV.”

Different is something that Jonathan Meades is. His fiction is certainly not formulaic. His television is far from being run-of-the-mill. His mind has the elements of wonder and curiosity of a young child, and the cutting intellect of a polymath with wide-ranging experiences. He uses words well, though it is hard to sum him up with them…

‘Etymological’ is an interesting word, sounds so much like ‘entomology’ that some people mite (sic) get confused, it’s the word for the study of words, how post-modern and self-referential is that? Of course, Meades would never get confused by this sort of thing, being an expert etymological archaeologist and Media Magus… I wonder does he have a favourite word?

“No.”

No? ‘No’ – that’s his favourite word? (Titles spring to mind for this interview feature: Jonathan Meades – the man who likes to say NO… Doctor NO… Mr NO it all… NO Meades NO… Or did he actually say, ‘Know’? Now, that’s more like it…)

“No, it’s not. I really don’t have a favourite word!”

- Thank you, Jonathan Meades!

Jonathan Meades was talking with Remy Dean

if you enjoyed this interview, you can...

and

No comments:

Post a Comment